Text of Colorado Law 2005 Commencement Address

Restoration of the Republic: the Usefulness of Citizens

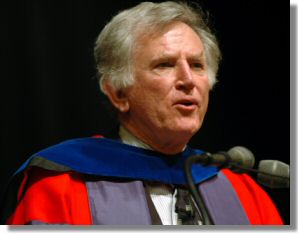

Gary Hart

University of Colorado Law School Commencement

May 6, 2005

For a dangerous mission behind British lines in 1775, General George Washington sought volunteers from a group of young officers. One stepped forward. His name was Nathan Hale. He said simply: “I wish to be useful.”

Later this summer most of you will pass the bar exam. Because I went to a law school--unlike Colorado--a law school that taught not what the law was but what the law out to be, when I took the bar exam 40 years ago this summer I answered the examiners’ questions by telling them what Colorado law ought to be.

They did not seem interested in what I thought the law ought to be, and so they invited me back the next session and I successfully told them what the law was and now have one of those increasingly rare Colorado law licenses numbered in the mid four digits..

The next step then for most of you will be to take the oath of office in order to approach the bar and practice law. That oath reads, in part: “I will use my knowledge of the law for the betterment of society….”

Why should lawyers have to take an oath to practice their profession when neither business people, teachers, truck drivers, nor practically anyone else has to swear an oath to do what they do?

The answer is, of course, not only that the practice of law is a solemn profession but also that a lawyer is an officer of the court, a peculiar kind of citizen with one foot in the private, commercial world and the other foot in one of the three Constitutionally recognized branches of government, the judicial.

So, whether you particularly like it or not, you are going to be semi-officially in the public arena. I’ve been around your generation enough to know that you do not particularly have high regard for politics. Too often there are reasons to understand why you might feel that way. But keep one thing in mind. You may not be interested in politics, but politics is interested in you.

By becoming an officer of the court, you already have one foot in the public life of your community, your society, and your nation.

Today I want to challenge you to take that position seriously and, at least for some of you, to think about putting the other foot in that arena for at least a portion of your lives, to say to some future national leader–even if not a George Washington–I wish to be useful.

I’ve heard the rumor, whether ugly or not, that one or two of you here may have chosen the legal profession because you figured it was a pretty sure path to comfort, ease, and wealth. That may or may not prove true in your careers but there are plenty of examples, such as my law school classmate Robert Rubin, former chairman of Goldman-Sachs, to encourage the possibility. But keep in mind in his case, as in the case of others, he went on to be one of the better Secretaries of the Treasury in modern times. He wanted to be useful. And he surely was.

The dean and faculty wish you all the very best in becoming productive participants in our commercial economy. The creation of wealth, whether your clients or your own, is to be encouraged. You might find a nation that provides a better chance to create private wealth than this one, but you would have to step outside the rule of law to do so.

Being citizens of the most successful and durable democracy in human history provides Constitutionally guaranteed rights–not just of speech, worship, and assembly, but also protection of property-- known to few other societies or nations.

My generation, the generation of the second half of the twentieth century, will, I hope, be known to history as the generation of the expansion of rights. We fought for civil rights for black Americans and all minorities. We demanded equality for women. We began to champion the rights of those who didn’t fit simplistic gender molds. We introduced the era of environmental rights. And the rights of those with disabilities. We were the first generation of Americans to take the rights promised in a democratic Constitution literally.

There are a few now in power who seem to wish to roll this era back and restore the limited democracy available primarily to white, property-owning, straight males. I pray you do not let them succeed. To prevent history’s pendulum from swinging back to the past, this is certainly an arena in which you can say, I wish to be useful.

But if we are a democracy of rights, why then do we pledge allegiance to the flag of the United States and the Republic for which it stands? What does it actually mean to be a republic?

Most of our Founders actually feared democracy and even rejected the language of democracy. For Hamilton, Adams, and Franklin democracy meant mobs in the streets, the worst excesses of the French revolution, a threat to political and social stability. They preferred the ideal and language of the republic, for which they had recourse to Athens and the Greek city-state some 2600 years before. Jefferson and many of the others read and wrote classical Greek and Latin. And, finding roots in Machiavelli’s Renaissance and the Enlightenment of Locke and the Scottish thinkers, they sought to recreate the ideal of the republic, albeit a federated republic on an unprecedented scale, on the new continent.

It was a breathtaking experiment, one that demanded resort not only to the language of the republic but also to its qualities and ideals. Republics throughout history have required certain qualities: civic virtue; popular sovereignty; resistance to corruption by special interests; and a sense of the common good. Held up to classical standards, the twenty-first century American Republic falls far short of this ideal and threatens to fall even further.

Even in the minimal civic virtue of voting we are derelict. And we hate to pay taxes even for necessary public services we all use.

We may favor foreign military adventures, particularly to secure oil supplies for our cars, but we do not particularly want our sons and daughters serving in the military.

We forfeit our sovereignty to special interest groups who gain access to power by huge campaign contributions. These special interest lobbying groups corrupt our system by placing their interests ahead of the common good. And thus we lose sight of the national interest and the common good..

Indeed, our self-absorption with our own rights and interests endangers our very national security. The U.S. Commission on National Security in the 21st Century, which I co-chaired, identified what it called “an unprecedented crisis of competence in government.”

And our Commission found that: “the quality of personnel serving in government is critically important to U.S. national security in the 21st century,” and that “a national campaign to reinvigorate and enhance the prestige of service to the nation is necessary.”

Today and for the rest of your lives I want you to seriously contemplate what it means to be a citizen of a republic. For, in contrast to a democracy of rights, the American Republic, like all republics, is a republic of duties.

It is no accident that Jefferson called his party, the first American political party, the Democratic Republican party. America seeks to combine both sides of the coin, a democracy of rights and a republic of duties. Its political philosophy, and my political philosophy, is simply stated: You must earn your rights by performance of your duties. It is this philosophy that led Nathan Hale and many patriots to follow over the next 220 years to say, I wish to be useful.

My argument today is not an abstract one. The American Republic is in jeopardy–not from communism, as in the twentieth century, or even from terrorism in the twenty-first century–but from within. There are those in government and in the academy today who believe America has no choice but to become an empire. They believe this is particularly true in the Middle East.

There are only two things wrong with this idea: Its proponents do not honestly reveal their imperial ambition to the American people who would surely see it for what it is and reject it. And it is impossible for America, as it has been impossible for all republics, to be at once an empire and a republic.

It is by no means accidental that America as empire is advocated when America as republic is on the wane. One has only to look at first century B.C. Rome to understand the correlation. The decline of civic duty, the surrender of popular sovereignty, the corruption by special interests, and the loss of the common good all mark the transition from republic to empire.

For the ideals of the republic, an empire substitutes domination of foreign lands, highly centralized powers of government, great costs of administration of foreign occupied lands, and the imposition of our will and often our cultural values on others.

None of these qualities describes a republic and they must not come to describe the American Republic.

As officers of the court you will have the duty to participate in the operations of the judicial system. But as you are lawyers professionally, you are also citizens personally. And as you have duties to the judicial system, you will also have duties to the republic.

The first and foremost duty is to help resist the temptations of empire and to restore the ideal of the American republic. This duty cannot be devolved on others. It cannot be deputized to an all volunteer force. It cannot be left to the career politicians. This duty is yours, and it is your highest duty.

For ancient republicans the title of citizen was the highest and most noble title. It carried with it rights. But it carried with it duties also. The exercise of those duties demonstrated civic virtue.

In an age whose politics is almost overwhelmed with the abstract language of “values,” very little attention is paid to the value of civic virtue, or to the value of the citizen’s duty to the republic whose flag we salute and to which we pledge our allegiance.

Let the family, the society, and the academy shape our personal and private values. Let our places of worship shape our religious values. But let the republic and its demand for civic virtue shape our public values.

The values in greatest need, and perhaps in greatest peril, today are the ancient values of courage, of honor, of integrity, and of duty. You will choose--if not everyday then often in your lives--whether to demonstrate these virtues or to conform, whether to go along to get along or to do what is right, whether to lose yourself in the crowd or whether to take the lonely path of honor--and thus to seek to achieve genuine nobility.

I have come here today to challenge you not merely to seek professional success but also to seek that nobility--a nobility not of ancient title but a nobility of service to the American Republic.

The way to set your course toward this goal is to greet each day with the simple declaration, to yourself and to your nation, “I wish to be useful.”

|

||||

| Gary Hart | ||||

| 2005 Commencement Speaker |

|

||||

| Gary Hart | ||||

| Spring 2005 Commencement Address |